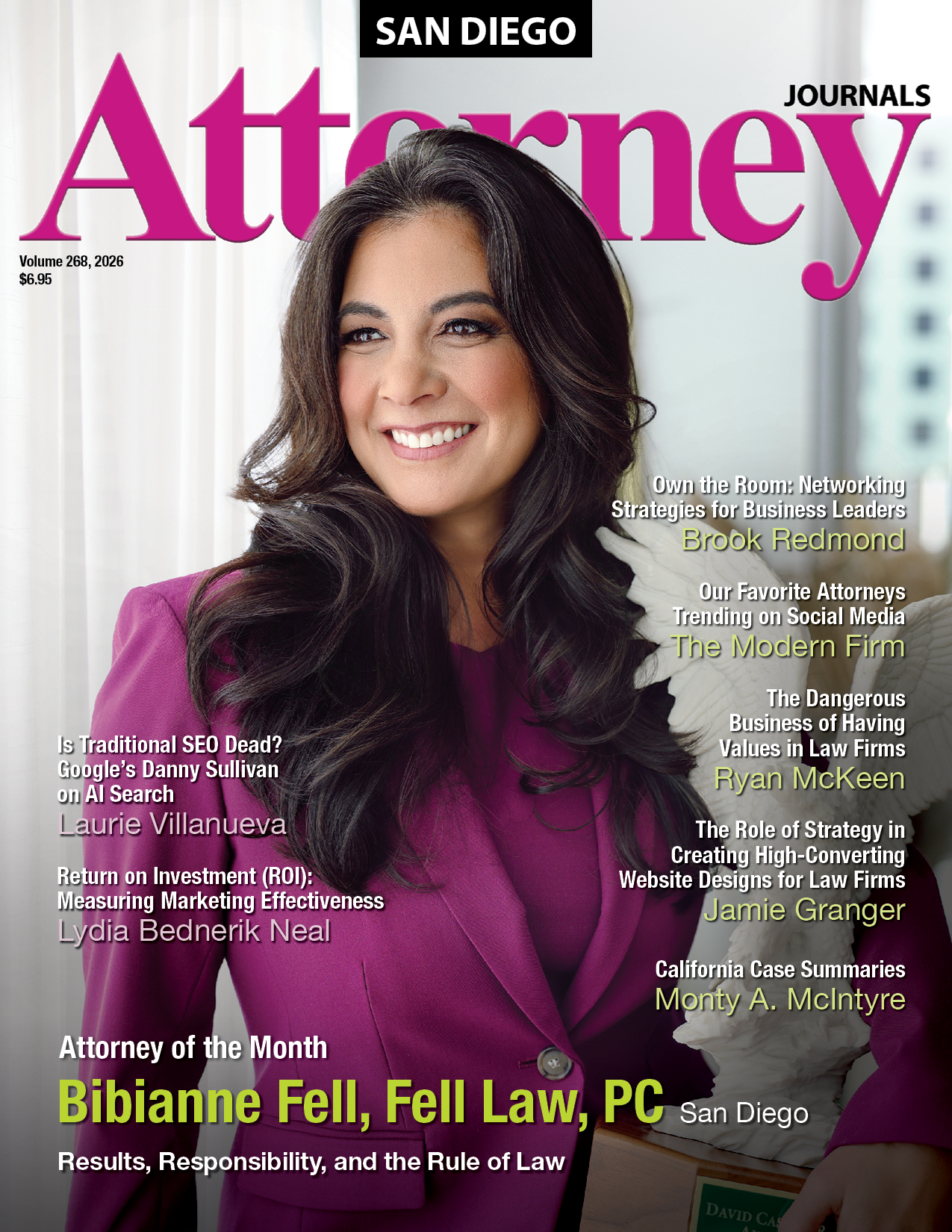

Attorney Journals is a Southern California B2B trade publication for and about private practice attorneys. The magazine brings information and news to the legal community as well as providing a platform to spotlight the people, events and happenings of the industry. But that's not all. From marketing advice to business and personal development tips, we're the top resource you need to thrive in the ever-evolving and highly competitive legal industry.

The Latest Stories, Tips and Buzz!

Law is, by nature, a conservative profession. It relies heavily on precedent and procedure, and its focus is often on minimizing liability or penalizing deviation from established rules. All of that adds up to a professional culture that values tradition over experimentation, and the known over the novel. Yet the legal profession does change. It wasn’t all that long ago that the only way to file pleadings or appear in court was in person. As technology evolves ever more quickly, the legal profession adapts and evolves with it. The attorneys who adapt the quickest often benefit the most. That’s true when it comes to the use of social media, too. Using social media in legal marketing may not be traditional, but it’s becoming increasingly common. Done right, it can improve your law firm’s online visibility, establish you as a trusted authority, and build trust with your prospective clients. And prospective clients aren’t the only ones who can form a positive opinion of your firm from your social media. Increasingly, AI models are integrating a law firm’s social media presence, including the content, followers, and commentary, into their “opinion” of the firm. Brendan Chard, owner of The Modern Firm, observes that “AI models take in more information (about a law firm) than just the website; they’re trying to determine the collective community opinion of a business. So a strong social media presence can contribute very positively on that front.” With those considerations in mind, let’s take a look at law firms that are using social media to their best advantage, and to their audience’s. McCune Law Group McCune Law Group, a plaintiff-side litigation firm in California’s Inland Empire, handles class actions and high-stakes lawsuits. The firm uses its social media to highlight its expertise, educate the public, and show a human side to its hard-driving practice. McCune Law Group produces popular educational videos answering questions such as “What if multiple parties are responsible for my injury?” and “Can I sue about a vehicle defect if there has already been a recall?” but their most popular videos are those with a comedic edge, like Taylor Swift lyrics translated into legalese. Why It Works: This firm utilizes its social channels to show potential clients that they have the knowledge and skill to prevail in complex litigation, but also wants those same individual clients to feel comfortable approaching the firm. McCune Law Group’s deft use of social media allows the firm to achieve both goals. Platforms: Facebook, X, LinkedIn, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube Muth Law, P.C. Muth Law, an Ann Arbor, Michigan-based personal injury law firm, uses its social media to showcase the many facets of the firm’s personality in a way that a website alone cannot. The firm’s Instagram posts are a mix of education that touches on the firm’s practice areas (e.g., “3 Essential Pictures to Take at a Car Accident Scene”); testimonials from clients; safety tips; notes about upcoming community events; weird Michigan laws; and good-natured fun (like blindfolding the boss and having him guess what Halloween candy he’s just been given to taste). Why It Works: It’s one thing for a law firm to state explicitly that “We’re knowledgeable; we’re community-minded; we’re friendly.” Muth Law doesn’t just tell viewers those things; they show them. Viewers get a glimpse behind the scenes of the firm, which builds trust. The frequent references to community events and Michigan-specific themes reinforce the firm’s image as a trusted, approachable local practice. Muth Law also gets bonus points for using AI-friendly formats, such as lists and question-and-answer dialogue in many written posts, increasing the posts’ engagement and visibility. Platforms: Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn The Kennedy Law Firm, PLLC The Kennedy Law Firm, a full-service practice with three offices in Clarksville, Tennessee, handles legal issues that are daunting for its clients: personal injury, bankruptcy, criminal defense, and more. This consumer-facing firm prides itself on being available and compassionate to clients going through one of the most challenging times in their lives. The firm uses its multiple social media channels in different ways: Facebook is primarily a platform for sharing firm updates, community involvement, and client testimonials. But by far the firm’s most popular social media platforms are Instagram and TikTok, with over 250,000 and 1.9 million followers. Why so many? Attorney Kevin Kennedy’s flashy, eye-catching style, featuring suit jackets so vibrant they’d make a peacock jealous, diamond pinky rings, and more than a little sass. Why It Works: Kennedy’s outrageous videos get shared like juicy gossip, and they inspire curiosity: Who is this lawyer? Viewers naturally head for the website, where they find a team of experienced, dedicated lawyers who know their craft and care about their clients. Platforms: Instagram, TikTok, Facebook Funes Law Group Immigration attorney Daniel Funes of Funes Law Group in Miami, Florida isn’t flashy or funny, but he uses his social media to great effect across multiple platforms, with content directed toward his primarily Spanish-speaking target audience. The firm’s social media content strategy focuses on providing valuable insight into immigration laws and procedures, with client testimonials and posts about the firm’s community involvement rounding out the mix. With a primary focus on TikTok and sharing of their high-quality, Spanish-language video content on other platforms, Funes Law Group is getting plenty of attention; it’s been recognized as one of the 500 fastest-growing firms across the United States. Why It Works: Daniel Funes understands his target market and what they need, and he speaks their language (literally), providing clear, concise answers to the questions that really matter to them. His social media success is due not only to his educational content and visually appealing videos, but also the fact that his social media team posts his messages on a consistent basis, building trust in the firm as they do so. Platforms: TikTok, Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube Martinez Immigration Attorney Kathleen Martinez of Martinez Immigration in Texas serves clients in all 50 states, and her millions of followers on social media attest to the reach of her message. With platinum blonde hair and a penchant for pink, Martinez has a distinctive visual brand echoed through both her social media and her firm’s hot pink website. But Martinez isn’t just another pretty face; she stays on top of the latest immigration news in Texas and beyond, and uses her social media platforms to update viewers on developments with straightforward language and actionable information. Why It Works: Martinez has a carefully cultivated brand, and it’s instantly recognizable across all of her social media, setting her apart from competitors. Brand recognition equals instant trust, and consistency drives engagement; followers know what to expect, which encourages likes, shares, and comments. Platforms: Instagram, TikTok, YouTube What Attorneys With Social Media Success Have in Common The attorneys above are very different: they span different practice areas and operate in different markets; they vary in age and following. Some take an educational approach, others a humorous one, and still others a blend. But they have a few very important things in common, and those things are critical to any law firm’s social media success: They Know Their Purpose and Audience As Yogi Berra said, “If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll end up somewhere else.” That’s a risk that attorneys who value their professional image can’t afford to take. Attorneys who are successful on social media never post without knowing who they’re trying to reach, what they want to say, and what they hope to achieve. They Offer Content That Matters To Their Audience Social media posts by attorneys that are too “sales-y” or self-promotional tend to fall flat; who wants to watch an advertisement, much less share it? The most successful posts provide useful information, entertainment, or a glimpse into the firm’s personality; sometimes, all three. They’re Authentic Lawyers can seem intimidating; social media posts that show a lawyer’s personality can make them seem more approachable. Don’t try to emulate what’s worked for other attorneys; viewers can detect inauthenticity from a mile away and it will backfire on your marketing. Oscar Wilde was onto something when he said, “Be yourself; everyone else is taken.” They’re Consistent Regular posting, ideally 1-3 times per week, helps you stay visible and helps your viewers stay engaged. Regular posting also helps viewers feel like they know you, which builds trust. They Respect Ethics Rules and Confidentiality Talking about real-life legal cases is one way to educate viewers on social media, but be careful not to run afoul of ethics rules regarding client confidentiality. Steer clear of discussing ongoing cases or using clients’ names or images. It should also go without saying to never give personal legal advice to individual followers. Keep your content general; it will keep you out of ethical trouble and appeal to a broader audience. They Get The Help They Need Establishing a thriving, engaging social media presence for your law firm takes more time than you may have available, and an understanding of the various platforms you may lack. That doesn’t mean social media success is out of reach. You may just need to build out your team to include professionals who can fill those gaps, develop a social media marketing plan tailored to your unique firm, or create video content for lawyers. Develop a Social Media Presence That Reflects Your Firm’s Brand In the end, using social media is just another way to help your target audience get to know your firm and put their trust in you when they need an attorney. Takeaways Information from a law firm’s social media is increasingly being incorporated into AI “opinions” about the firm. To succeed on social media, law firms must define their goals and understand their audience. Authenticity is key for law firms that want to build trust and engagement on social media. The social media posts that succeed are those with valuable, relatable content, not self-promotion. Consistent visual branding helps attorneys stand out on social media. When posting on social media, law firms must remain mindful of confidentiality and attorney advertising rules.

The Wu-Tang Clan taught us that “cash rules everything around me.” And nowhere is this truer than in law firms. I have learned a lot about people over the last two years. I have been through a lot. I have been betrayed by people I trusted. And I have been uplifted by people who possess a genuine moral compass and an authentic sense of values. Separating the posers from the real ones has been an unexpected gift in a long battle. Here is what I have learned: It is dangerous to come between people and money. Most people will choose money every single time. This is not cynicism. This is observation. And if you want to understand why law firms struggle with culture, why toxic partners survive for decades, why meaningful reform feels impossible, you need to understand this fundamental truth about human nature and economic incentives. The Economics of Looking Away Law firms are money-making machines. This is not a criticism. It is simply a fact. Partners eat what they kill. Compensation depends on origination credits, billable hours, and business development. Every relationship has a dollar sign attached to it. This creates a problem when values and profit collide. Good people will excuse awful behavior if they think addressing it will cost them money or the opportunity to make money. They won’t endorse the behavior. They will simply look the other way. I have watched this happen repeatedly. Sexual harassment. Bullying. Substance abuse. Partners who treat associates like disposable labor. Rainmakers who create hostile work environments. The pattern is always the same. People know. People see. People stay quiet. Why? Because that partner brings in three million dollars a year. Because that practice group generates twenty percent of the firm’s revenue. Because confronting the problem means risking the relationship and risking the money. This is how monsters survive in professional environments. Harvey Weinstein operated for decades. Diddy operated for decades. Otherwise, decent people knew something was wrong and said nothing. Fear played a role. But so did greed. Speaking up meant risking access. Risking opportunity. Risking the next deal. Law firms operate on the same dynamics, just at a smaller scale and with lower stakes. The partner who screams at associates? Everyone knows. The partner who makes inappropriate comments? Everyone knows. The partner who takes credit for other people’s work? Everyone knows. And everyone stays quiet because the math is simple. Confrontation equals risk. Silence equals continued compensation. The Convenient Lie This dynamic makes it easy for people to believe lies that serve their interests. When someone challenges a powerful person, the firm faces a choice. Investigate genuinely and risk losing a rainmaker or accept a convenient narrative that protects the revenue stream. I have watched otherwise intelligent people embrace obvious falsehoods because the truth was expensive. Liars understand this. They craft narratives designed for a receptive audience. An audience that wants to believe. An audience that has financial incentives to believe. This is not stupidity. It is motivated reasoning. People are remarkably good at convincing themselves that what benefits them financially is also what is true and right. The partner accused of harassment? There must be another explanation. The associate who complained? Probably a performance issue. The pattern of behavior spanning years and multiple victims? Coincidence. Convenient lies require cooperative believers. Law firms are full of them. What Values Actually Mean Here is what I have learned about values: They are what you do when it is inconvenient and does not maximize profit. Anyone can have values when values cost nothing. Anyone can stand for integrity when integrity is easy. The test comes when standing for something means losing something. Most people fail this test. They will profess values up to and until those values cost them money. Then the rationalizations begin. Then the exceptions emerge. Then the principles that seemed so firm suddenly become flexible. I am not saying this to condemn anyone. I am saying this because understanding it is essential to understanding how law firms actually work. When a firm says it values diversity but promotes the same demographic year after year, what does it actually value? When a firm says it values work-life balance but rewards partners who bill 2400 hours, what does it actually value? When a firm says it values respect but tolerates a partner who demeans staff, what does it actually value? The answer is always the same. Firms value what they pay for. Everything else is marketing. The Danger of Speaking Truth Telling the truth is rarely convenient. Speaking up that something is wrong is only safe when the wrongdoer is weak. If they are in power, you are in trouble. I have lived this. Speaking truth to power in a law firm environment is career-threatening behavior. The person who raises concerns becomes the problem. The whistleblower becomes the troublemaker. The truth-teller becomes the one who lacks judgment. This is not an accident. It is a feature of the system. Power protects itself by punishing those who challenge it. And in law firms, power is measured in dollars. The associate who reports a partner’s misconduct faces retaliation. The partner who challenges another partner’s behavior faces political consequences. The staff member who refuses to participate in something unethical faces termination. Meanwhile, the person with power faces nothing. Because they generate revenue. Because they have relationships. Because removing them costs money. This creates a brutal calculus for anyone with a conscience. Speak up and risk everything. Stay quiet and keep your career intact. Most people choose their careers. I do not blame them. I understand the choice even when I disagree with it. Control Mechanisms Abusive systems require control mechanisms. Law firms have plenty. Compensation structures are control mechanisms. When your income depends on the discretion of a small group of people, you learn quickly not to challenge that group. Origination credits are control mechanisms. When credit for business can be allocated or taken away based on relationships, you learn to maintain relationships even with people who behave badly. Awards and recognition are control mechanisms. Who gets nominated? Who gets celebrated? These decisions signal what the firm actually values and who holds power. Partnership decisions are the ultimate control mechanism. Years of work leading to a single vote by people whose favor you need. How likely are you to rock the boat during that process? These mechanisms are not inherently evil. But they create environments where abuse can flourish. Where silence becomes rational. Where going along becomes safer than speaking up. The Silence That Enables Abuse depends on silence. The silence of victims, yes. But more importantly, the silence of bystanders. There is a quote often attributed to Dante, though the sourcing is disputed: “The hottest places in Hell are reserved for those who, in times of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality.” Whether Dante said it or not, the sentiment is true. Neutrality in the face of wrongdoing is not neutral. It is support for the wrongdoer. Every person who sees something wrong and says nothing makes it easier for that wrong to continue. Law firms are full of neutral people. People who know something is wrong. People who have the standing to speak up. People who choose not to because the personal cost is too high. I have been one of those people. I have seen things and said nothing because the timing was not right. Because I needed something from someone. Because I was afraid. I am not proud of it. But I have also been the person who spoke up. Who challenged power. Who refused to go along. And I have paid for it. Every single time. The Leadership Problem Here is the hard truth that nobody wants to acknowledge: All problems in a law firm are leadership problems. Toxic partners exist because leadership allows them to exist. Bad culture persists because leadership permits it to persist. Values get compromised because leadership compromises them. When a firm tolerates behavior that contradicts its stated values, that is a leadership decision. When a firm protects a rainmaker at the expense of everyone else, that is a leadership decision. When a firm chooses revenue over integrity, that is a leadership decision. Healthy law firms are those with values-driven leadership. Leaders who make hard decisions. Leaders who remove toxic people even when it costs money. Leaders who demonstrate through action that certain behaviors are unacceptable regardless of how much business someone brings in. These firms exist. They are rare. They are almost always led by people who have decided that some things matter more than maximizing profit. Evil Is Real I have come to believe that evil exists in the world. Not cartoon evil. Not mustache-twirling villainy. Ordinary evil. The evil of people who do harm because they can. Because it benefits them. Because nobody stops them. Evil banks on greed. Evil banks on self-interest. Evil banks on weak people who will not stand in its way. Law firms are not uniquely evil places. But they are places where the incentives align in ways that let bad actors thrive. Where the structures protect power. Where the economics reward silence. If you work in a law firm, you will eventually face a moment where your values and your interests conflict. You will have to decide who you actually are. Most people discover they are weaker than they thought. Some people discover they are stronger. Either way, you will learn something about yourself. I have learned a lot about myself over the last two years. I have learned what I will tolerate and what I will not. I have learned what I will sacrifice to maintain my integrity. I have learned who my real friends are. And I have learned that speaking truth in law firms is dangerous business. It remains worth doing anyway. Not because it will be rewarded. Not because it will be easy. But because some things matter more than money. The Wu-Tang Clan was right. Cash rules everything around us. But it does not have to rule us.

In today’s digital-first world, your law firm’s website is more than just a virtual brochure—it’s your most powerful marketing asset. Yet, I’ve encountered countless law firm websites that failed to convert visitors into leads, not because of poor aesthetics, but because of a missing ingredient: strategy. A high-converting website doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the product of thoughtful planning, intentional design, and a deep understanding of your clients’ journey. So how can strategic thinking transform your firm’s website from a digital placeholder into a client-generating machine? 1. Understanding Your Ideal Client The foundation of any strategic design process is clarity around who your ideal client is. Are you targeting high-net-worth individuals seeking estate planning? Startups needing intellectual property support? Injury victims looking for justice? By defining your target audience, your website’s tone, content, and layout can speak directly to their concerns. Strategic design begins by understanding your potential clients’ pain points, goals, and decision-making process—and aligning your messaging to meet them where they are. 2. Mapping the Client Journey Every visitor arrives at your site with a problem. Your job is to guide them through a path that leads to a solution—and ultimately, to contact you. This journey typically follows a structure: Awareness: The client identifies a legal issue. Consideration: They explore potential solutions. Decision: They choose the right lawyer or firm. Strategic websites map this path and structure the design around it. Clear navigation, trust-building content (like testimonials and case results), and obvious calls to action help move users smoothly from curiosity to conversion. 3. Prioritizing User Experience (UX) No matter how visually striking your site is, if users can’t easily find information or contact you, they’ll leave. Strategic UX focuses on: Fast loading times Mobile responsiveness Logical page hierarchy Accessible forms and contact methods For law firms, where trust and professionalism are critical, a frictionless experience signals reliability and competence. 4. Content With Purpose Every word on your site should serve a goal—whether it’s to inform, persuade, or prompt action. Strategic content includes: SEO-driven practice area pages that not only attract traffic but also address pressing legal questions and showcase your firm’s experience and successful representations. Clear, benefit-focused headlines that immediately show visitors how your firm can solve their problem or improve their situation. FAQs that address common client questions in plain, conversational language—helping potential clients become informed while aligning with natural search queries. Blog content that answers high-intent client questions, builds authority, and links directly to related practice area pages. Rather than flooding the site with legal jargon, strategic content speaks clearly and confidently, helping potential clients feel informed and empowered. 5. Law Firm Website Design That Supports Conversion Design isn’t just about looking good—it’s about guiding behavior. A strategically designed law firm website achieves that with: Prominent calls to action (“Schedule a Consultation,” “Speak to an Attorney”) Visual hierarchy that leads the eye Strategic placement of trust elements (badges, reviews, affiliations) The layout should drive engagement and build confidence, no matter how users navigate your site. 6. Data-Driven Improvements Strategy doesn’t stop at launch. A high-converting law firm website is constantly evolving based on: Heatmaps and click tracking A/B testing headlines or call-to-action buttons Analytics on user behavior and bounce rates Law firms that approach their website as a living, data-informed asset consistently outperform those with static, set-it-and-forget-it designs. Final Thoughts The most successful law firm websites are built on strategy, not guesswork. They combine design, content, and user experience into a unified system that converts visitors into inquiries—and inquiries into clients. In a competitive legal landscape, simply having a website isn’t enough. To truly stand out and grow your practice, you need a strategic approach to design that puts client needs, clarity, and conversion at the center.

CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL Arbitration LaCour v. Marshalls of California (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3731034: The Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s order denying defendant’s motion to compel arbitration of a former employee plaintiff’s single-count PAGA action. In denying the motion, the trial court reasoned that “there is no such thing as an ‘individual PAGA claim’ ” that could be severed and compelled to arbitration. The Court of Appeal affirmed, holding that—based on ordinary contract-interpretation principles and the parties’ mutual intent when the arbitration agreement was signed in 2014—the arbitration agreement did not clearly reflect an agreement to arbitrate “individual PAGA claims,” so defendant was not entitled to compel arbitration notwithstanding Viking River Cruises, Inc. v. Moriana (2022) 596 U.S. 639 and related post-Viking River developments. (C.A. 1st, Dec. 24, 2025.) Attorney Fees Evleshin v. Meyer (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3101271: The Court of Appeal reversed the trial court’s order denying defendants’ postjudgment motion for attorney fees. Following a bench trial the trial court entered judgment in favor of defendants, the sellers of a Santa Cruz home, and found them to be the prevailing parties in a lawsuit filed by plaintiffs/buyers alleging breach of contract and fraud. In the purchase agreement the parties agreed to mediate if there was a dispute. If one party refused to mediate they would lose the right to recover attorney fees if they later prevailed. Based upon these provisions, the trial court denied defendants’ motion for attorney fees on the grounds that defendants had refused to mediate, and although they were the prevailing they had lost the ability to recover attorney fees. The Court of Appeal disagreed, concluding that the trial court erred in reading the contract’s mediation clause to impose a forfeiture where there was evidence in the record that could support a conclusion that while defendants’ initially declined to mediate, they re-opened the door to mediation before the lawsuit was filed. The case was remanded for further proceedings. If the trial court finds on remand that defendants retracted their initial refusal to mediate and expressed a willingness to mediate before the lawsuit was filed, the disentitlement provision in the contract would not apply. (C.A. 6th, November 6, 2025.) Johnson v. Rubylin, Inc. (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3687544: The Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s decision sanctioning plaintiff for failing to comply with Civil Code section 55.54(d)(7) by refusing to disclose in his early-evaluation-conference statement the amount of attorney fees and costs he was claiming as of that time, and—after offering an alternative sanction of proceeding but not being able to recover attorney fees—dismissed the action with prejudice when plaintiff elected dismissal. The Court of Appeal affirmed, holding that section 55.54(d)(7)’s requirement to disclose claimed attorney fees and costs did not violate the attorney-client privilege (distinguishing the decision in Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors v. Superior Court (2016) 2 Cal.5th 282). It also concluded the trial court’s sanctions procedure did not violate due process. (C.A. 6th, December 19, 2025.) Employment Dobarro v. Kim (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3228546: The Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s decision denying defendant’s appeal of a Labor Commissioner wage award to plaintiff because it was filed one day late. The trial court concluded the notice of appeal was untimely filed under Labor Code section 98.2. The Court of Appeal affirmed, concluding that the Labor Code section 98.2 deadlines for appealing a Labor Commissioner decision and for posting or seeking waiver of the undertaking are mandatory and jurisdictional, not subject to equitable tolling or the electronic-filing tolling provision in Code of Civil Procedure section 1010.6, rejected defendant’s other arguments as meritless, declined to impose sanctions but published the opinion to clarify the law. (C.A. 1st, November 19, 2025.) Torts Gilliland v. City of Pleasanton (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3225067: The Court of Appeal reversed the trial court’s finding for defendant, in a bench trial on the liability of defendant under the immunity provided in Vehicle Code section 17004.7, in plaintiff’s action for personal injuries suffered when her car was hit by another driver who was being followed by a city police officer. The trial court concluded that defendant’s written vehicular pursuit policy and training complied with the statute and the other driver Elijah Henry believed he was being pursued, thereby rendering defendant immune from liability for plaintiff’s injuries and entering judgment in defendant’s favor. The Court of Appeal disagreed, concluding that held the term “pursued” in section 17004.7(b)(1) must be given a single meaning derived from the vehicular pursuit definition in the public entity’s policy (including the requirement that the suspect be attempting to avoid arrest), and the trial court applied the wrong legal standard in assessing Henry’s belief and improperly disregarded evidence that he did not think he was being pursued under that policy. The case was reversed and remanded for reconsideration of defendant’s the immunity claim under the correct standard. (C.A. 1st, November 19, 2025.) Trial McDonald v. Zargaryan (2025) _ Cal.App.5th _ , 2025 WL 3704598: The Court of Appeal reversed the judgment for plaintiff, following a jury trial, where the jury awarded plaintiff future medical expenses of $1,872,900, past pain and suffering of $2 million, and for future pain and suffering was $10 million. The issue in this case was the fact that plaintiff first went to see a surgeon, Dr. Toorag Gravori, the week before trial and 16 months after the exchange of expert information. Seven days before trial, counsel for plaintiff blindsided the defense with a new medical expert with a new medical theory. The trial court denied defendants’ motion in limine to exclude plaintiff’s late-disclosed medical expert, permitted the expert to testify after an expedited deposition, and the jury returned the substantial verdict above for plaintiff that the court reduced to judgment. The Court of Appeal held the trial court abused its discretion by allowing the surprise expert to testify despite plaintiff’s failure to timely disclose the expert or seek leave to augment the expert list and the absence of any reasonable justification for the eve-of-trial designation. The judgment was vacated and the case was remanded for a new trial. (C.A. 2nd, December 22, 2025.)

Networking is not simply a social exercise. It is a core business skill. The ability to build trust, strengthen relationships, and create meaningful connections is essential to leadership success. Whether you are attending an industry conference, client reception, or company event, approaching networking with intention allows you to show up confidently and make every interaction count. Below are eight practical strategies to help you navigate any room with purpose and polish. Prepare With Intention. Effective networking begins well before you arrive. Review the event agenda and attendee list when available, and identify a few individuals you would like to meet. Learn about their roles or recent initiatives to uncover shared interests or potential synergies. Set a goal for the event, whether reconnecting with a client, expanding your industry network, or staying informed on market trends. Prepare a few open-ended conversation starters, such as “What developments are you seeing in your sector this year?” Make a Strong First Impression. Your first impression sets the tone. Enter the room with confidence by standing tall, making eye contact, and offering a warm smile. A composed, approachable presence signals professionalism and credibility before the first word is spoken. Refine Your Introduction. A confident introduction makes conversations feel natural and focused. In 20 to 30 seconds, share who you are, what you do, and the value you bring to your organization. For example, “I am [Name], and I work with [Company]’s legal team supporting strategic decision-making while ensuring regulatory alignment. My focus is on translating complex legal issues into practical business solutions that help drive growth.” Keep it conversational and tailor it to the audience. End with an invitation to engage, such as “What about you? What’s your role, and what’s been exciting in your work lately?” Build Rapport Through Authentic Conversation. While small talk opens the door, genuine connection comes from meaningful exchange. Start with the event or industry news and then transition to professional interests. Sharing a thoughtful perspective or personal insight makes interactions more memorable and fosters trust. Allow the conversation to unfold naturally and avoid overly personal questions. Listen With Purpose. The most impactful networkers are excellent listeners. Maintain eye contact, offer thoughtful follow-up questions, and stay fully present by putting technology aside during conversations. Demonstrating authentic interest builds rapport and makes others feel valued, which strengthens professional connections. People remember how you made them feel, and genuine interest builds trust. Position Yourself Strategically. A few logistical details can enhance your networking flow. Wear your name badge on your right side so it is easy to see during introductions, and keep your right hand free for greeting. If you arrive alone, begin near natural conversation hubs such as the registration desk or refreshment area. These spaces create easy opportunities to engage organically. Exit Conversations With Grace. Knowing how to transition elegantly is as important as the introduction. Thank your conversation partner and suggest a natural next step, such as connecting on LinkedIn, continuing the discussion by email, or meeting for coffee. Introducing them to another attendee is also a thoughtful way to expand mutual connections before moving on. Follow Up to Strengthen Connections. True networking happens after the event. Send a personalized message within 48 hours referencing something specific from your conversation. Connect on LinkedIn with a brief note. Share relevant insights or introduce them to a helpful contact. Consistent, genuine follow-up transforms brief encounters into long-term professional relationships. The Bottom Line Owning the room does not mean being the loudest voice. It means being intentional, confident, and authentic. Preparation, presence, and thoughtful follow-up empower you to turn everyday networking moments into lasting business relationships.

Do you know how effective this marketing tactic is? How much profit (or loss) is attributed to a specific marketing expense—what’s my ROI? It’s a question we get asked every day. Understanding the return on your investment (ROI) can be tricky. Especially in professional services, most clients’ hiring decisions are based on a combination of factors, so it can be difficult to attribute a new client to one specific marketing line item. Often a potential client will become aware of your services in multiple ways, frequently through a referral from a trusted friend or business associate, perhaps building a relationship with you over time and eventually hiring you when an immediate need presents itself. Firms want to understand the best places to spend limited marketing dollars. For very large firms, it may make sense to put sophisticated tracking mechanisms into place for determining the relative contributions of various marketing tactics to the client development process. For smaller shops, a few basic and manageable measures may prove helpful enough without creating an undue burden. The following are a few guiding thoughts. Begin With the End in Mind At the start of each marketing campaign or activity, ask yourself what success will look like. What is the business driver for your campaign? Are you trying to drive revenue for a specific type of work? Increase traffic to your website? Do you need to recruit talented associates? Are you supporting a succession plan to transfer firm ownership to the next generation of leaders? How we measure marketing and public relations results has evolved over the years. As digital platforms offer increasingly sophisticated tracking insights, there are new data points and ways to measure online results. But “real world” activities require a more human touch. In any case, you don’t have to measure everything possible to gain useful insights into the effectiveness of your marketing spend. Instead, start with a few manageable objectives that support your overall business goals and build on them over time. Define Your Goals If your goal is to increase traffic to your website, think through the why, the how, and, most importantly, the where. Is your inbound traffic visiting the right pages of your site to take the next step in their journey with you? Set up key event goals to track in Google Analytics 4 (which has replaced Universal Analytics). In addition to looking at simple site visits, track where and how long people spend time on your site. Did they follow a call to action (CTA), such as downloading information, filling out a form, or contacting the firm? If you invest in a conference exhibit booth, plan ways to track the number (and quality) of attendee contacts made during the event. Were you able to convert these people into LinkedIn connections, newsletter subscribers, follow-up calls, or other measurable post-event activities? A firm can look at successful results through many different lenses, each as one stepping stone to building practice success. Tracking Whatever your ultimate goal, you’ll need a way to track results. It’s helpful to start with a baseline prior to initiating your activity. For example, if your goal is to gain more clients in a particular practice, you’ll need to know how many matters you have in that area and where your clients have come from historically. If you haven’t been tracking referral sources in the past, do the best you can to gather the information and then begin a system for tracking this going forward. The most common way would be to have a “Referred by” field or two associated with your intake process. Ask every potential client how they found you, even if they don’t end up hiring you. You’ll want a way to generate reports based on this information, whether as part of an accounting system, a contact relationship management platform (CRM) or a simple Excel spreadsheet. Reviewing your referred-by information at regular intervals, you can attach revenues generated (or projected) on those specific matters to determine the ROI of the marketing you do. Keep in mind, that the client may tell you that their accountant referred you, but you’ll want to try to understand how that accountant met you in the first place. Perhaps it was because you spoke at an accounting industry event or met them through a networking forum. Those insights will help you to identify the ROI of your various activities. Depending on the volume of data you will need to digest, track, and report, it may be beneficial to standardize some information. For example, you might want to have a set of general categories on which you can sort and filter, such as “Print Ads,” “Organic Internet Search,” and “Conferences,” as well as a freeform field for additional information, such as the name and firm name of a specific referral source or the name and year of the conference or advertising campaign. Memories will fade, so the more specific you are now, the better your future decision-making will be. Quantity vs. Quality Many traditional (and even current digital) sales funnel principles are developed from a consumer products (and services) perspective. This model assumes that casting a very wide net (i.e., being in front of a high volume of eyeballs) will equate to higher sales. For some aspects of your marketing, this may offer some useful guidance. Especially if you run a practice that relies on reaching clients who are likely to use your services only once, such as personal injury or consumer bankruptcy. In these cases, you can look at the cost of, for example, a pay-per-click (PPC) campaign and track how many qualified leads contact your office based on that campaign. Then, determine how many of those contacts convert into actual clients. Of course, there is a lot that happens between those two events, so make sure you are not making false assumptions about effectiveness. For example, if many people contact your office based on an advertisement, but you don’t respond to the majority of them until three days after initial contact, most of those people probably won’t become clients. In that case, the activity generated from your marketing spend might be high (demonstrating a high ROI for driving clients to the firm), but your lack of follow-through may be crushing your conversion rate (creating a low ROI when measuring the number of actual new clients gained). Many legal practices and B2B services have long sales cycles. These firms may need to spend more dollars (and time) on long-tail initiatives that deepen relationships with key referral sources or concentrate on building impressive credentials for their attorneys showcasing niche expertise. While it is rare that publishing a single article in an industry trade publication will cause the phone to ring with a new client, having that publication listed on an attorney’s bio will likely be an influencing factor in their assessment of the attorney’s expertise. These types of activities will be harder to attribute individually to a specific client acquisition. However, they are worthwhile as contributing factors, making their cumulative effect very powerful. In these cases, the most important measure may not be the number of reader impressions with potential clients or referral sources, but rather ensuring that the activities are targeted to engage the right specific people with hiring or influencing authority—typically a small subset of individuals. Measuring What Matters There are nearly limitless metrics you can use to determine whether a marketing campaign is effectively supporting your goals. Here are a few more ways to think about the question of ROI. If the firm is expanding into a new geography, is your marketing generating new leads originating from that location? Are website visitors engaging with content that is specifically relevant to that location? If the firm places digital ads with a publication, have you set them up with tracking links so you can see the number of visitors that come to your website directly by clicking on that ad? Are you testing and tracking different versions to continuously improve on your results? If you want to showcase niche expertise, have you increased the volume of content published on the topic (via blogs, article placements, podcast appearances, videos or other media)? Are you leveraging that content across multiple platforms? How are your audiences engaging with that content? Final Thoughts Be patient. Remember that marketing requires consistency. Just because you become bored with your campaign and are ready to move on to the next shiny marketing object doesn’t mean that you’ve even scratched the surface of market penetration. Some say that it takes seven impressions before your audience will consciously process your advertising message. Of course, having the right solution communicated to a potential client exactly when they need that particular service is the secret sauce. Since you rarely know when that is going to be, having a consistent presence is the key. The value of any marketing activity is ultimately how well it helps support your business goals. You don’t have to address all of the aspects discussed above with a complete overhaul of your marketing program, especially if you are a small team or managing a limited budget (and let’s be honest, who isn’t?). Rather, identify one goal, build a targeted campaign around that, and measure it (ideally, you’ll have a baseline based on historical data). Try new things, measure, analyze, and adjust. If you aren’t seeing the needle move after a reasonable period, try something different. The better you focus your marketing and business development activities in support of specific firm goals, the more you will realize a positive return on your marketing investments.